Making Sense: Calligrapher 李佩亭 Peiting C. Li

On materiality, devotion to practice, and why calligraphy is like dance

Peiting C. Li is the most unpretentious aesthete I’ve ever met. I’m lucky to call the talented calligrapher a dear friend. Peiting is an artist, educator, researcher (for her PhD she studied the history of medicine in China, making her an excellent companion when visiting botanical gardens or herb shops), a student of guitar, and an admirer of all things beautiful. I was thrilled to join her at her Berkeley studio, where she lives and practices her art surrounded by stacks of books.

Kate: When I first met you, it was clear that material was important to you. In your art form, but just on an everyday level, it shows up in your outfits. You’re always wearing special jewelry, like your bangles.

Peiting: Because they remind me of the past and certain people. So this belonged to my great-grandmother.

Is it jade?

Yes. Jade. This has been passed down in my family for at least four generations, if not more. In Chinese culture, there’s a belief that jade absorbs the energy, the 氣 qi, of the person who wears it. Sometimes I feel like I don’t know if I can do something. And then my mom is reminds me “ you know, your great grandmother was actually very resilient, and she’s with you.” And that’s very powerful.

When we cowork together sometimes, you always have this small object you keep with you on the desk while you work.

So the idea for it came from a poet named Rick Tibbetts. He said that he always takes something portable as a little signal to bring him into a state of work or flow, a little touchstone. And so I’d always remember that. For a while I used these small stones. And then I went to this store down the street, Tibetan Arts, and I don’t know what it was about this particular thing that drew me. Maybe because it’s a mixture of dots and lines, which are the constituent elements of calligraphy. It has a certain heft and weight and seeing it helps me focus. I keep it in my pocket.

What sense are you engaging with the most when you’re doing calligraphy?

It’s primarily visual, but I’m pretty nearsighted and I have this eye condition that requires a lot of effort to focus. And so for the past ten years I’ve suffered from eye strain. For a while, I would be really down about not being able to practice. And recently I decided I’m still going to practice even if I can’t see that well. So sometimes I practice without my glasses on. And it’s sort of expanding what I would consider a primarily visual practice into one that’s also about touch.

You’ve written about how sound and smell are important clues in your art form, too.

Can I show you what grinding the ink sounds like?

“Grinding ink emits a subtle earthy scent that the ready-made stuff lacks. Inksticks and inkstones of good quality together produce a quiet but distinct sound, reminiscent of a muted singing bowl.”

-Peiting C. Li, “Speak, Ink”

In the same essay, you said calligraphy isn’t so much like painting or drawing. It’s actually closer to dancing.

That’s what my calligraphy teacher in Shanghai told me. It’s because calligraphy is a lot about movement and time. In the sense that what you see when you look at someone’s calligraphy is the record of movement in time because of the sensitivity of materials. You see how the brush moves on the paper and generally it’s one stroke. So sometimes people look at Chinese calligraphy or writing and they think it’s like Western painting. Like, oh, I go up here then let me do a little more, or touch it up. But dance, my understanding when I’ve seen it, is it’s very much one gesture at a time. And once it’s over, it’s over. You don’t go back and go like, oh, I, yeah, I meant to do the splits, but let me just extend a little longer. So that’s why I think [calligraphy] has a strong affinity with dance because both are the product of a lot of practice and repetition.

Right, you can’t just endlessly be refining.

“Every nervous wobble, uncertain pause, and wayward brush hair registers immediately on the paper. There is no going back to fix, no erasing. To produce even a somewhat beautifully shaped dot or a steady line requires many years, and many tears. These materials seem purposely designed to stymie those who want to write immediately and reward only those committed to many years of practice.”

-Peiting C. Li, “Speak, Ink”

Right. Although there are other pieces of work where part of the beauty is seeing the… I don’t know if I would say mistakes, but the changes that the person has made in the drafting. One of the most famous pieces of calligraphy, Wang Xizhi’s “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion,” is like that, and it’s not perfect, but it’s revered for its improvisational spirit, in form and content. It’s about a particular gathering in the fourth century of some literati playing a drinking game. The game entailed taking a cup of alcohol and floating it down a stream. And when the cup stopped in front of you, you had to compose some poetry. And if you couldn’t come up with something, then you'd have to drink as a punishment. So calligraphy has both sides. It has the extreme rigor where every stroke must be very beautifully controlled. But also something that is more spontaneous and free.

How did you first come to calligraphy as an art form?

My parents are both from Taiwan, and I attended weekend Chinese school as a kid, so I knew about it to an extent, but had never taken a class or anything. Eventually I quit Chinese school, but when I was in high school, I decided I wanted to learn Chinese again. Then, in college, I started studying Chinese language and went to Taiwan for a language program. After my masters, I returned to Taiwan for an advanced language program and while I was there, I took a calligraphy elective class for a few weeks. At the time, I was already thinking of doing a PhD in Chinese history. And on the first day of that calligraphy class, this teacher wrote a poem for each of us, in the characters of our names as the first and last characters in the poem. So it begins with 佩 pei “esteemed” or “admirable” (originally literally meaning a type of jade) and ends with ting 亭 “pavilion.”

So I kept this paper, and thought maybe one day I’ll try calligraphy more seriously. But my academic obligations felt too heavy, so I put it off for 8 years.

When I saw the teacher writing, and when I thought about calligraphy in general, it just seemed like no, that’s too hard. Just the amount of discipline and time it would take, it just seemed impossible.

I always hate the word discipline because it’s connected with so much nastiness for me. I can be so critical. So I’m always trying to think of other words…

Yeah, what did I read the other day? Something about commitment or devotion..

Devotion I like.

I like it, too. Because the thing about discipline, you’re right, there’s this hard edge to it. When I first started calligraphy, I would come home and keep practicing until 2:00 AM. So I’d just throw time at it. And I feel like now, especially as I’m older and my body has changed and my eyes get tired more easily, I’m a little more gentle with myself. Even if I didn’t “ practice” today or I only did a few minutes, that still counts.

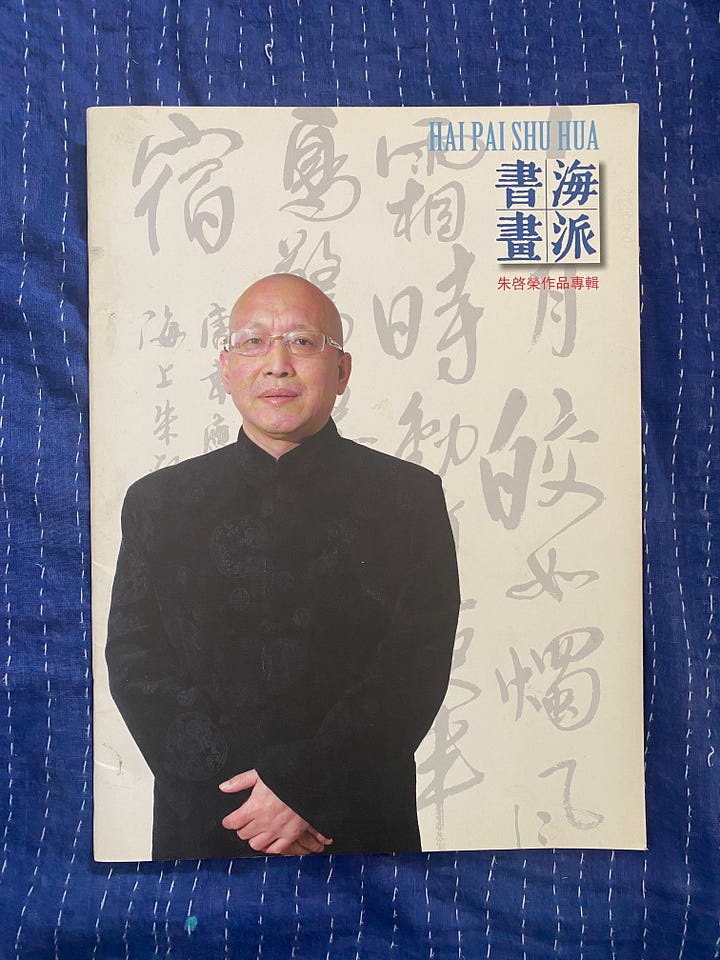

You meet yourself where you’re at. I know you studied with a calligraphy teacher in Shanghai, and he influenced your ideas of discipline.

Oh gosh, he’s amazing.

He changed my life. I saw him once or twice a week for about two months and he would not accept any form of payment from me. We talked about calligraphy, but it became a vehicle for talking about everything else. I remember he said you ostensibly you come to me to learn about brush work and aesthetics, but we’re really talking about life.

What came up when you were practicing with him that felt more about life than about the art of calligraphy?

The recognition of my initial response or natural tendency towards things in general. So for example, I would ask him what to do when my hand would shake. And he said, yeah, it’s really common. This happens to a lot of students, and sometimes it’s just going to take time. And there are micro adjustments you can make. So, I realized that rather than stay in this state of like, Oh my God, this is so uncomfortable, I could look at it from a few different angles and that really helped me. I noticed that I have that tendency in other parts of my life to be like, Oh, I can’t do that. Like total panic. For example, I can’t apply for a job there because I have no car and I can’t take all my stuff on my bike. I would anticipate all these obstacles ahead of time.

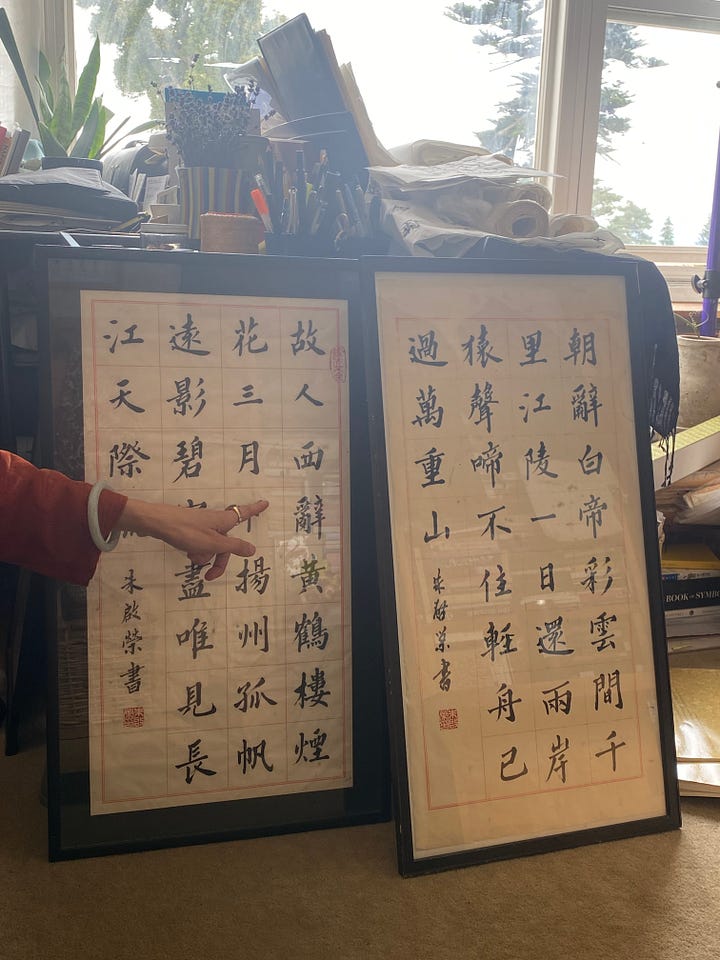

I still think about my Shanghai teacher. There was a point in time where I would look at like the curve of one line and get a little teary eyed because of the subtle beauty of his lines. The way that this kind of curves up very gently? (Peiting points to her teacher’s artwork.) That’s so hard to do.

That’s so beautiful. As a person who has never practiced this, I would have no idea how difficult it is to do each of these movements.

It’s not only the movement, but to get the contrast between thick and thin and back to thick where it trails off like that? The control. It’s so, so hard.

[Calligraphy] is a mirror. It shows you all of your tendencies, like perfectionism. For me, I often have this narrative of I should be doing this every day for three hours. But if the reality of my life is that I can only manage five minutes right now, that’s good, that’s fine.

[Calligraphy] is a mirror. It shows you all of your tendencies

I recently had a lesson with another teacher in Tapei and he said there’s a difference between what is called 外功 waigong and 內功 neigong. Waigong means external effort, practice, for example looking at diagrams and technique. And neigong is the interior work. This teacher urged me not to neglect the interior work, which is your emotions, experiences, your relationships, and how all that finds expression on the page in ways that you don’t expect. He said sometimes you don’t even have to pick up your brush to practice. And that was freeing to hear.

People talk about this in the history of calligraphy, too. One of the most famous calligraphers supposedly said that his biggest breakthrough came after watching the flight patterns of birds. That’s another thing calligraphy has taught me is sometimes the most direct path is not necessarily the only way.

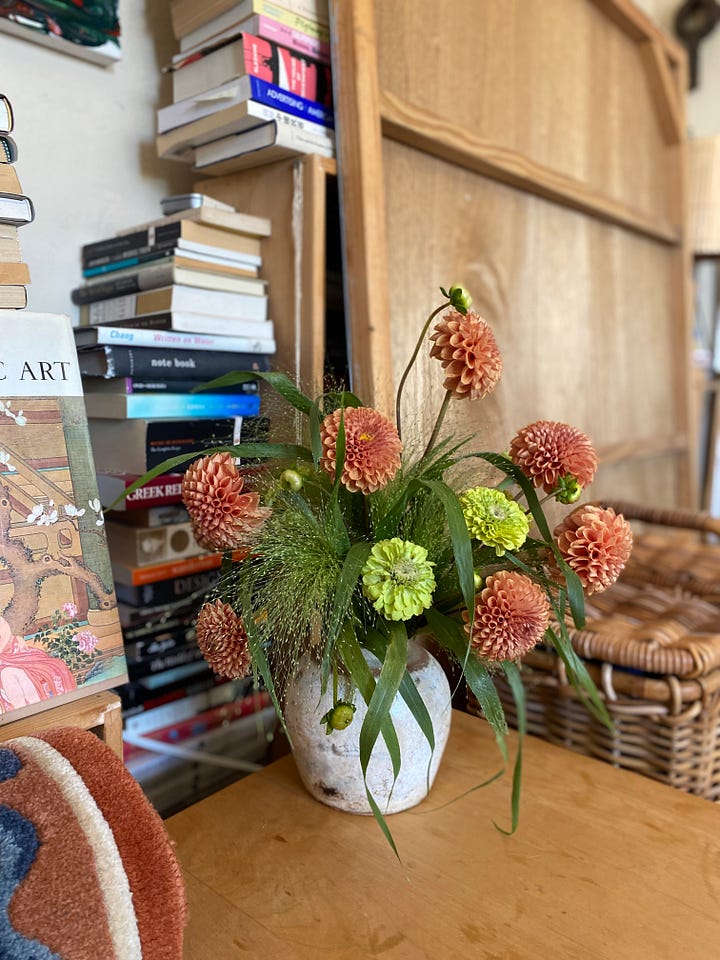

Peiting and I picked out her bouquet together at the San Francisco Flower Market. We chose explosion grass because of its dots and lines, the same key components of calligraphy. Peiting was also drawn to the combination of the lime green zinnias and rusty dahlias. I found an old Chinese ginger jar in her cabinet and repurposed it as a vessel.

Thank you, Peiting! For more from Peiting, check out her Instagram @peitingcalligraphy. For interested folks in the Bay Area, Peiting teaches calligraphy at the UC Berkeley Art Studio and biweekly at Teance. You don’t have to know Chinese to join and beginners are welcome!

Finally, here are some other sensory recommendations from Peiting:

Sound: The music of jazz pianist and composer Bill Evans – he nods to calligraphy in his liner notes on “Kind of Blue.”

These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.

Sight: The architect Christopher Alexander - his ideas about the modularity of living spaces influence how Peiting sets up her studio space with multi-functional furniture.

Intuition: She recommends following your intuition when the orchids call to you at the flower market, and taking home a gorgeous butterfly orchid.

Fascinating interview! Loved the bouquet mix & the long green leaves were a perfect choice for a calligrapher.

Loved this interview! Thank you